This North Dakotan successfully fought for prohibition and giving women the right to vote – InForum

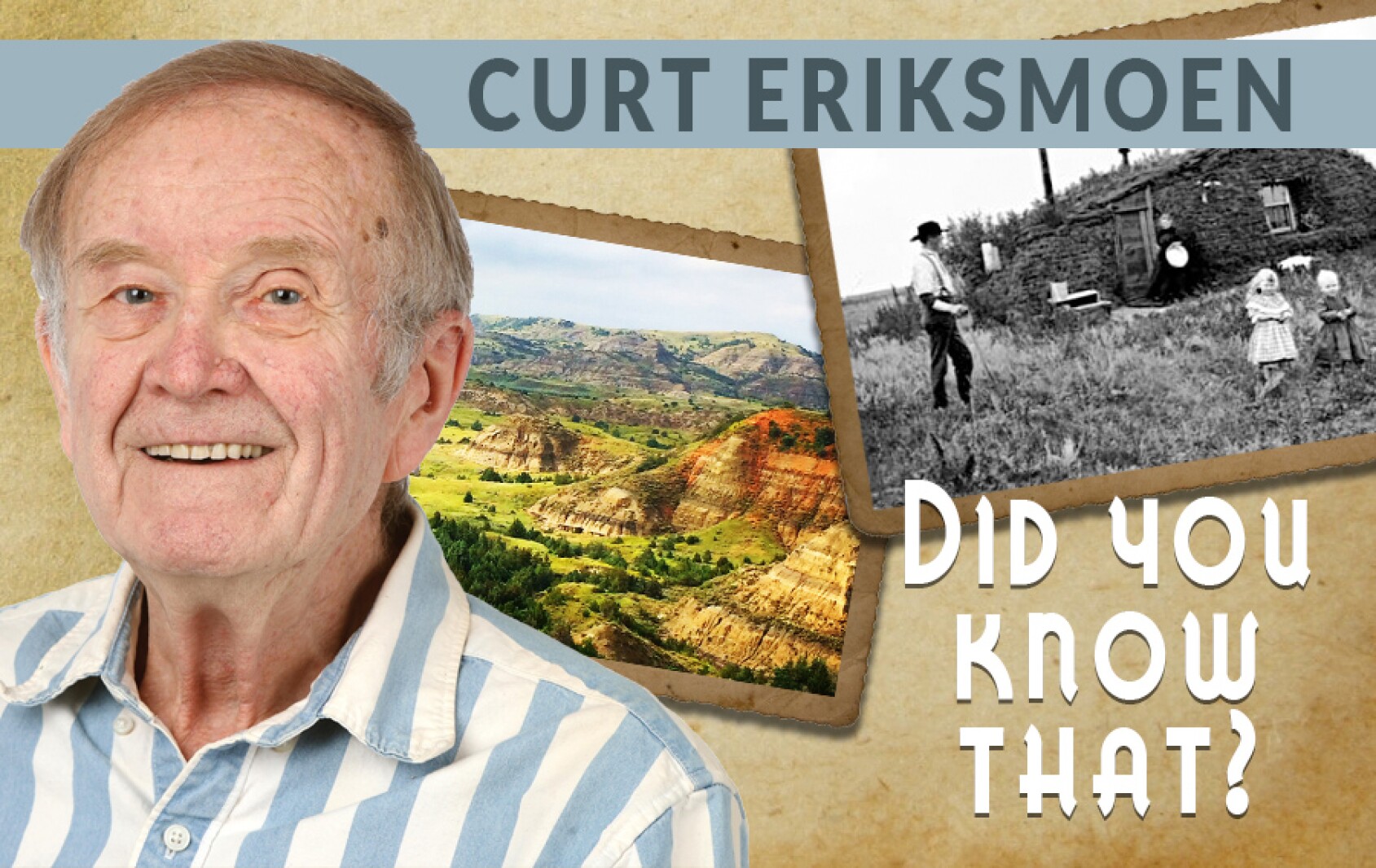

Editor’s note: This is the third and final story from InForum history columnist Curt Eriksmoen on the life of Elizabeth Preston Anderson. Miss Curt’s earlier stories? Read about Elizabeth’s

life as an early social reformer

and

her fight for women’s suffrage.

When North Dakota became a state in 1889, half of the adults in the state were not allowed to vote on almost all election issues. The newly adopted state constitution stated that “women could (only) vote on all school matters and hold office in school-related positions.”

Many of the women in North Dakota objected to being relegated to second-class citizenship status and the most influential organization to voice objection to this concern was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. One of the leading advocates for full women’s participation in all election matters was Elizabeth Preston, a former school teacher from Tower City.

In 1893, Elizabeth was elected president of the North Dakota WCTU and in early March she went to Bismarck to testify before the legislature. Elizabeth urged the legislators to support a bill that was introduced by Sen. James Stevens from Dickey County. The bill granted women the right to vote and it passed both the House and the Senate. However, after George Walsh, the Speaker of the House refused to sign it, the bill was lost before reaching Gov. Eli Shortridge’s desk. The House expunged any reference of its passage from the record.

Contributed / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

From 1895 to 1901, Elizabeth worked closely with the women’s organizations that championed suffrage for women. The first was the North Dakota Equal Suffrage Association, created by Cora and Sara Smith in 1895 in Grand Forks. When Cora, now Mrs. Robert Eaton, moved to Minneapolis in 1896 to become the chief surgeon at a maternity hospital, the center for the women’s suffrage movement shifted to Fargo. The prominent activists in Fargo were Clara Darrow, the wife of Dr. Edward Darrow, and their daughters, Elizabeth, and Mary. Helen deLendrecie,

the wife of a prominent Fargo businessman,

and Christine Pollock, the wife of a noted attorney from Casselton, were also notable activists in the NDESA in Fargo.

Elizabeth Preston attended the North Dakota legislative sessions in 1895, 1897, and 1899, where she lobbied the legislators to introduce and pass bills supporting women’s suffrage. She succeeded in getting a bill introduced in 1895, but it failed to pass. Then, from 1901 to 1911, Elizabeth succeeded in getting legislators to introduce women’s suffrage bills in all six sessions, but, each time, the bills were unsuccessful.

In 1901, she became Elizabeth Preston Anderson with her marriage to Reverend James Anderson, an Episcopal/Methodist pastor. Soon, Elizabeth began to receive national recognition for her excellent work with the North Dakota WCTU. In 1904, she became assistant secretary of the national WCTU and in 1906 she began her 20-year tenure as the WCTU national recording secretary.

In February 1912, Sylvia Pankhurst, a British suffragist, arrived in Fargo and held a meeting at the home of Mary Darrow Weible, daughter of Clara Darrow. The Darrow women organized Votes for Women Leagues in Fargo and Grand Forks and then organized a statewide suffrage convention in June 1912. At the convention, the suffrage leaders developed a strategy for getting women’s suffrage approved during the 1913 legislative session.

During the 1913 session, Elizabeth and members of the Votes for Women League met with key state legislators. Three suffrage bills were introduced, of which two passed both legislative bodies. One of those successful bills was drawn up by Sen. Harrison Bronson of Grand Forks. It would become a statutory measure that would be placed on a ballot in the 1914 general election, of which all the registered voters would be men. The other suffrage bill that was passed was introduced by Sen. John Cashel from Grafton. The Cashel bill proposed an amendment to the state constitution and, to become law, it would need to be approved again by the 1915 legislative assembly.

The passage of these two bills meant that within two years there would become two different ways that women could obtain the right to vote. There may have been optimism with some of those favoring women’s suffrage, but there was a great deal of concern for many. In 1914, an opposition organization was created called “The North Dakota Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage” which was headquartered in Fargo. Many people, particularly those of German descent, were angry because the WCTU and other women’s organizations were instrumental in imposing Prohibition on the state’s citizens.

Both sides of the women’s suffrage issue began to ramp up their campaigns in 1914. Suffragists campaigned by organizing suffrage clubs, securing favorable newspaper coverage and distributing pro-suffrage literature. It was estimated that 40,000 North Dakota women backed the Bronson bill. The major problem was that women could not vote. Furthermore, wording in the state constitution meant that those who did not vote “yes” were added to the “no” votes.

When the general election was conducted on Nov. 3, 1914, the issue failed by a vote of 40,209 to 49,348. Historians claim that if you subtracted those who did not vote on this issue, the margin would have been 12,000 votes in favor of women’s suffrage. When the Cashel amendment came up for a second vote in the 1915 legislature, it failed to pass because several legislators thought that the defeat of the measure in the 1914 general election meant that voters in the state opposed women’s suffrage.

Elizabeth Anderson may have experienced a setback, but she certainly did not feel defeated. In 1916, she contacted Robert M. Pollock, a prominent Casselton attorney who had recently moved his practice to Fargo. Pollock had been a member of the 1889 Constitutional Convention and was speaker of the House of Representatives in 1901. His wife Christine Pollock was an active advocate for women’s suffrage. Although Pollock’s bill only granted partial suffrage, Anderson and other suffrage leaders accepted it because they thought that it would easily pass and then they would have a foot in the door to eventual complete suffrage.

During the 1917 legislative session, Sen. Oscar Lindstrom of Burke County introduced the suffrage bill and it quickly passed both houses of the legislature. Women could now vote for President of the U.S. and most county and municipal officers but were still not permitted to vote for governor, state legislators or members of Congress. On Jan. 23, Gov. Lynn Frazier signed the presidential and municipal suffrage bill into law, with Anderson standing next to him.

Contributed / Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

On June 4, 1919, the U.S. Senate approved the 19th Amendment to the Constitution giving women the same voting privileges as men. The amendment needed to be approved before the next regular session, so Frazier called the legislature into a special session. Both houses of the North Dakota legislature overwhelmingly approved the amendment and Frazier signed the joint resolution on Dec. 5, 1919, and North Dakota became the 20th state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

Having secured her two major objectives, prohibition and women’s suffrage, Anderson spent much of the remaining 14 years as president of the North Dakota WCTU working on social and educational issues. She resigned as president in 1933 and, two years later, her husband Reverend James Anderson retired from his ministry. The couple then spent most of their time living in Detroit Lakes, Minnesota, and Florida. After James’s death in 1941, Elizabeth spent most of her time living with a stepson in Miles City, Montana, where she died on Nov. 30, 1954.